We’re usually more interested in what’s inside a book’s covers, but volumes bound with Morocco leather are some of the most elegant and valuable in the world. To understand how this binding material became the world standard for luxurious libraries, we need to travel to Fez, Morocco.

The Chouara Tannery

The beating heart of Fez is the old quarter or medina called Fes en-Bali, a labyrinth of narrow alleys packed with craftsmen selling their wares: spices (ras el hanout, saffron, cumin, turmeric, paprika, cinnamon, fenugreek), dates, hand-woven carpets, musical instruments, and handmade leather goods.

The acrid odor in the medina — a singular mix of ammonia and heat — will guide you to the leather shops that surround the three tanneries. Suddenly the handfuls of mint carried by tourists make sense, an improvised herbal breathing mask to filter the odors. At Chouara — the oldest tannery, reaching back in time almost 1000 years — the leather makers use the same technique as their medieval brethren. It’s a multi-step technique that involves soaking, stripping, and drying the hides multiple times before they’re submerged in vats of technicolor dyes.

The soaking steps of the process are responsible for the eye-searing smells: first, a wash of cow urine, quicklime, salt, and water; later, a blend of water and pigeon feces. The natural ammonia in animal waste acts as a tenderizer, eventually producing some of the softest, smoothest leather in the world.

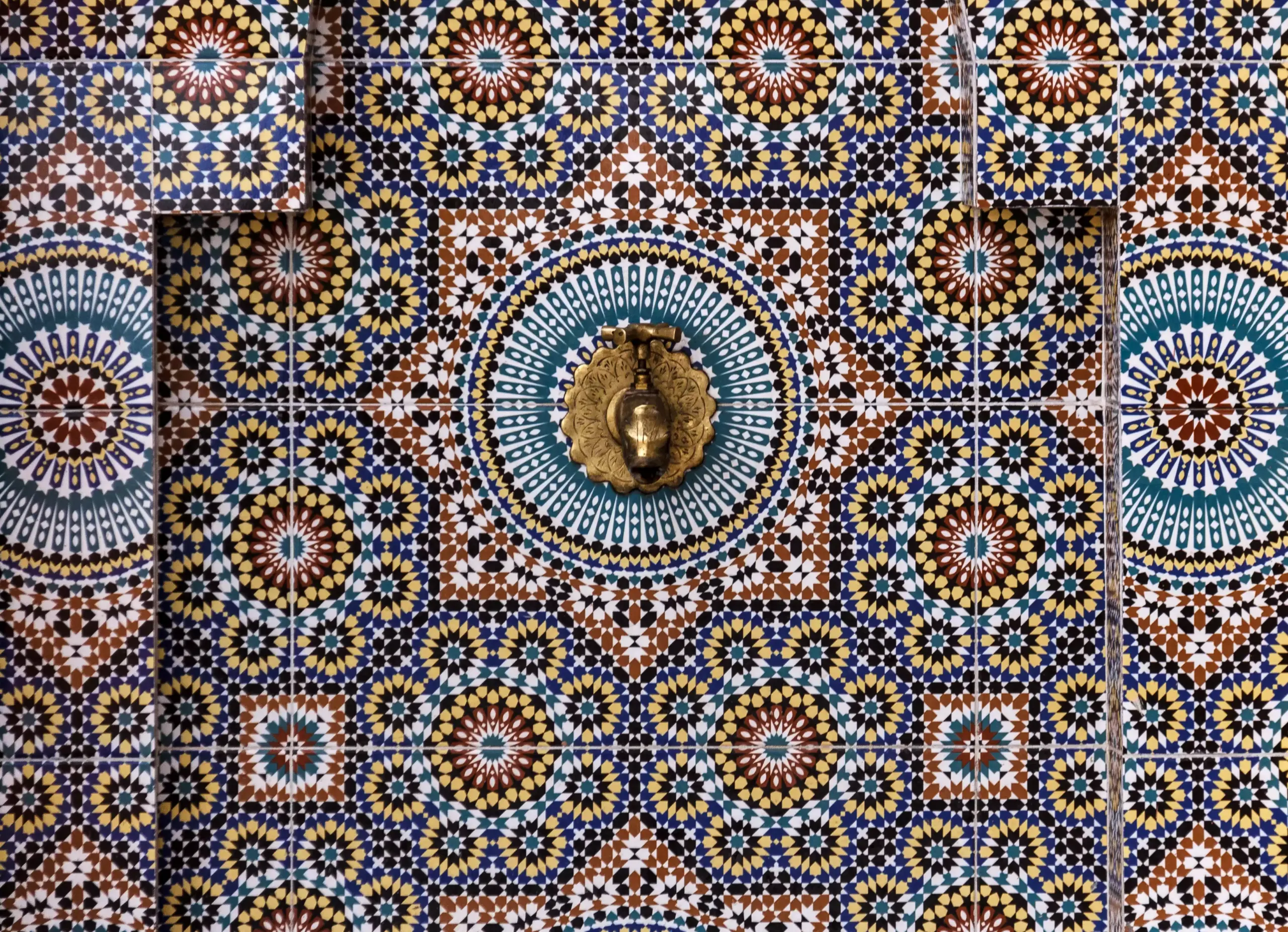

The hides swim in waist-deep, tile-lined earthenware vats. Men in bare feet and plastic pants stomp the skins for up to three hours before the leather is hung on ancient walls to dry in the sun. Donkeys carry the hides from the pastures outside the city and within the medina; stray cats slink around the vats, suspiciously eyeing the proceedings.

The dyes are made from local plants, and the colors are the palette of the desert: poppy flower (red), henna (orange), saffron (yellow), mint (green), indigo (blue), and cedarwood (brown). The resulting leather is transformed into pointy-toed slippers, known as babouches; handbags and satchels; jackets and gloves; wallets; and flexible sheets that can be folded into book covers.

Strong and supple

As early as the 7th century, the codex (bound book) was the standard to record and share the Qur’an. Around this time, Muslim conquests opened new trading routes in North Africa and Spain, and books became one of the most profitable goods. Eventually, other products from African markets traveled across the Strait of Gibraltar, including Morocco leather. By Shakespeare’s time, this supple leather became the deluxe choice for bookbindings; today, antiquarian books with Morocco leather bindings are still the most luxurious.

So what makes Morocco leather so special?

Traditional Morocco leather is made from goatskin, which is easily identified by its visible grain. The tanning process retains the pattern in the skins, so the resulting leather has a satisfying texture. Because goatskins more readily absorb dyes than sheep or cowhides, the colors of Moroccan leather are richer and more saturated. (Bauman’s Rare Books shows close-up comparisons of different types of leather.)

Goatskin is also thicker and more durable than other animal hides. The goatskins are pounded to make them thinner and more flexible, but the inherent toughness means a Morocco leather cover can endure being opened and closed thousands of times. The durability also lends itself to bedazzling with hand-tooled details like braid patterns, stars, rosettes, or fleurons; gold stamping; and even jewels. This is a stunning example of a 19th-century Morocco leather book with gilt, hand-tooled designs, and jeweled binding.